28 Apr Friday…The History of Modern Medical Science ( Part 4 )

When I was reading a witness statement from Witnesses To Modern Biomedicine I was amazed that until about 1965 there was an enormous amount of ignorance about pain and subsequently there was a lot of acute pain particularly in end of life situations and the thought that ‘men didn’t need powerful drugs’ for pain but women did, seems extraordinary.

A large percentage of us have usually experienced some form of severe pain or at least witnessed it as often it occurs at births and deaths.

And then when my father was in his last days in hospital he would suddenly have an attack of awful pain which was swiftly taken away by a dose of morphine…the magic of seeing that was incredible, and such a relief, to witness.

The relatively recent advancements of pain relief are something that I am personally so grateful for but also just amazed that it is possible.

The witness statement below is from Dame Cicely Saunders, physician and the founder of the Modern Hospice Movement

Going to St Joseph’s Hospice, which was virtually untouched by medical advance, I was able to introduce records and the regular giving of morphine, which they hadn’t started, and according to one of the sisters of the ward that I was first in, it was the change from painful to pain-free. Having been given four patients to look after, I was soon looking after every admission into those 45 beds. So I began keeping records in detail, pre-computer, on a punch card system, and making tape recordings of patients talking about their pain from 1960, and I realised that what we were looking at was what I described later, in 1964, as total pain. And I will quote from one patient, when I said to her, ‘Tell me about your pain, Mrs H.’ She just said, ‘Well, doctor, it began in my back, but now it seems that all of me is wrong. I could have cried for the pills and the injections, but I knew that I mustn’t. Nobody seemed to understand how I felt, and it seemed as if the whole world was against me. My husband and son were marvellous, but they would have to stay off work and lose their money, but it’s so wonderful to begin to feel safe again.’ And so she has really talked about the physical, the psychological, the social, and her spiritual need for security to look at who she was, coming to the end of her life. And for another patient it was, ‘All pain and now it’s gone, and I am free.’ It is not possible to treat pain in isolation. We have to consider the whole person.

and this one from Professor Duncan Vere, Clinical Pharmacologist

I will say that until about 1965 there was entrenched ignorance, a tremendous amount of severe pain. Patients who were in severe pain, or dying with pain, were often given the Brompton cocktail, or Mist. Obliterans, as it was politely known, and it was a matter of patients being rendered so that they didn’t know what they were doing, by doctors who certainly didn’t know what they were doing. They were using medicines with actions that they couldn’t understand, because they had this complex mixture of cocaine, morphine, gin, sometimes with phenothiazine added. Parsimony was the order of the day, which rendered control impossible. Pain breakthrough was frequent, and intermittent control is disastrous, if only for the reason of the self-augmentation of pain. Hospice care had, of course, begun but somehow it didn’t seem to have come across into the general medical and surgical field in hospitals and general practice.

I think for a lot of people the idea of hospitals is really terrifying particularly for births and deaths. I think it probably has a lot to do with the lack of comfort there, and consequently a prevention of relaxation. They’re public spaces after all, so I can absolutely understand why treatments at home would be preferable.

It was also really interesting to read about some of the advancements into home treatments, like Home Dialysis for example. The witness statements below are from parent and patient and actually illustrate the difficulties of coping with being treated at home;

Dr Jean Northover, Scientist and parent of Dialysis patient

Diana had two siblings and really dialysis had to be a normal part of the family pattern; it couldn’t take priority. The other two children needed attention. The last thing I would like to say is that the funny thing about home dialysis is that when we had got past the ten-year mark – we went on for about sixteen years before Diana got a transplant in 1985 – what we found was that you worked so hard and you had so little rest, that when finally you’d finished with the dialysis, the Kiil (part of the dialysis equipment) was put on the local dump and the transplant was working, you couldn’t really remember what you had been doing a lot of the time. So this was extreme, emotional, psychological, and mental fatigue. I don’t know what the two sides of the brain were playing at! But I kept a friendship going with another dialysis mother, and she said, ‘I need you as my witness, because I have got to talk to somebody, I have got to know that we really went through it.’ She suffered from the same thing. So when people say, ‘Oh, go and learn French by total immersion’, I have to say that what we learnt on home dialysis was certainly ‘home dialysis by total immersion’.

Mrs Diana Garratt, childhood Dialysis patient

I am a renal patient, started in 1969. It was January 1970 when Rosemarie Baillod came round to set me up at home on haemodialysis with my first shunt and I remember the room very well. We had a de-aerator, it looked like a toilet cistern, high on the wall above the bed. Actually, I think I was dialyzing on the table at that time, we hadn’t organized the bed. The rest of the family went on around us; we had a small TV, my younger brother and sister and the cat, who went very soon after because it was sitting there watching the pulsating blood lines and that was very nerve-wracking, very, very nerve-wracking. We got through it, but it was an enormous effort. Every day you were either on the kidney machine, or you were hoping that the machine, which was not at all reliable compared with the modern machines, would work, that the kidney would not burst, that you wouldn’t have a blood leak.

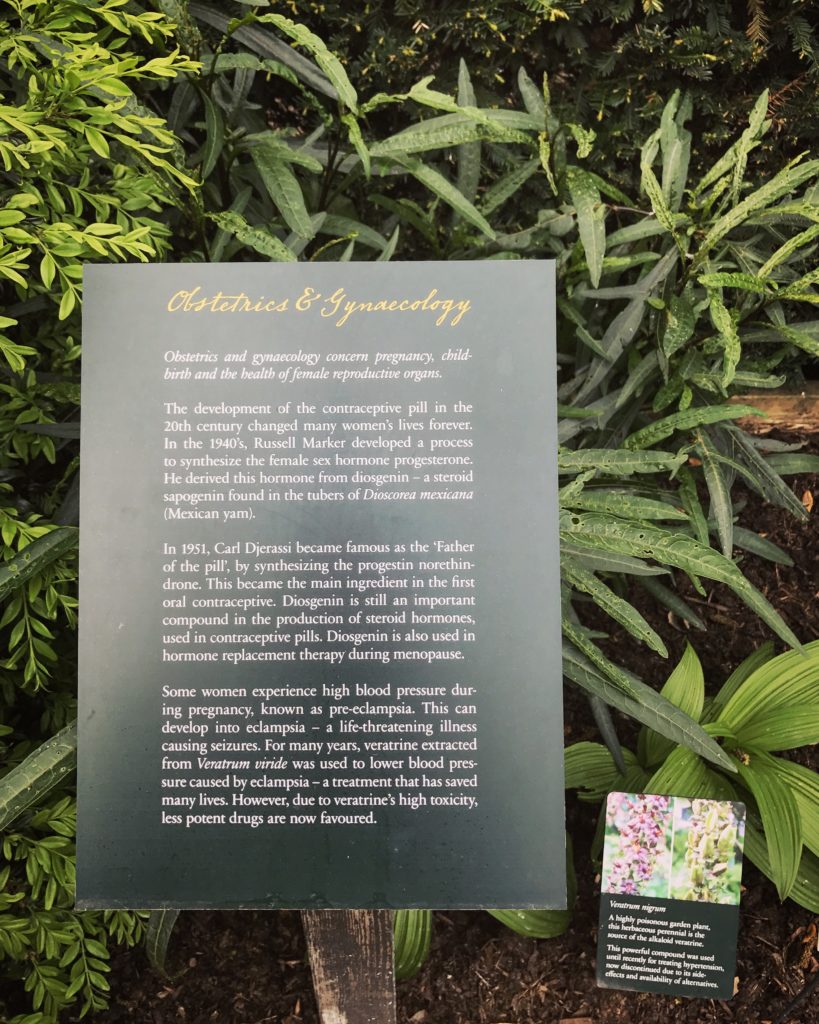

When I gave birth to my son, it was a tricky time and there was no way we’d both still be alive if I’d have had a home birth. I had the continual intrapartum fetal monitoring when I was in labour which worked out to our advantage so it was really interesting to read that in the 1960’s when that technology was in its infancy, the enthusiastic obstetricians and midwives carried screwdrivers in their top pockets so that they were able to adjust the temperamental new apparatus when required.

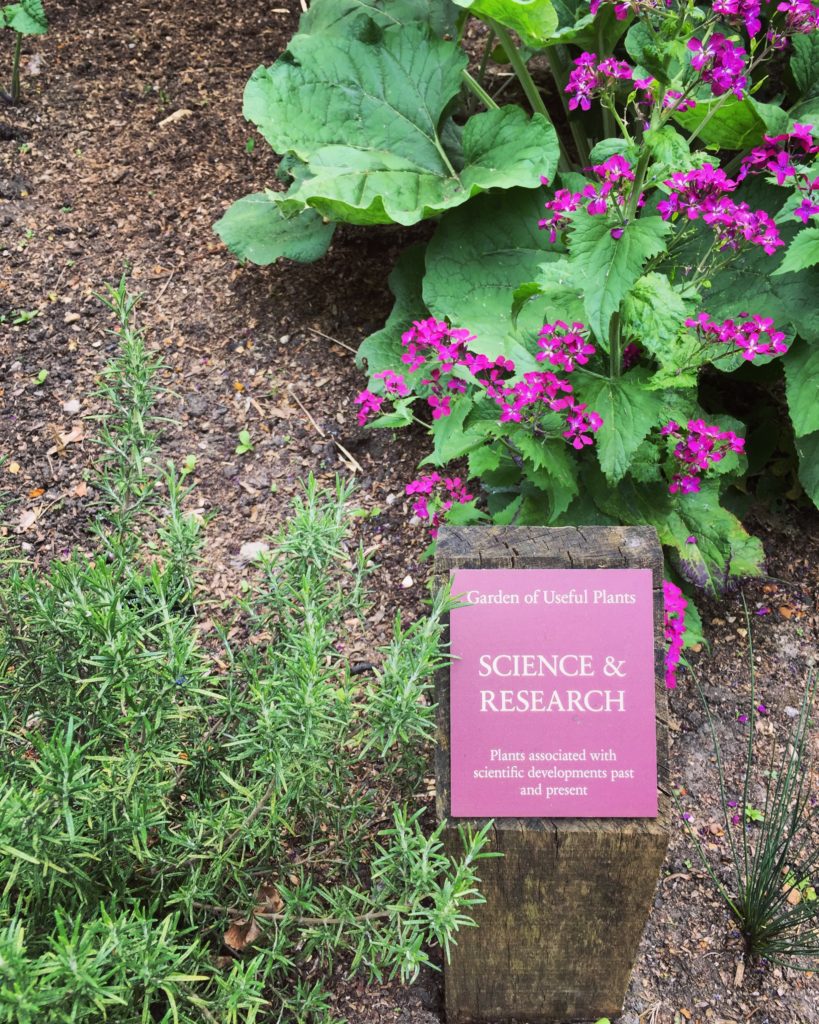

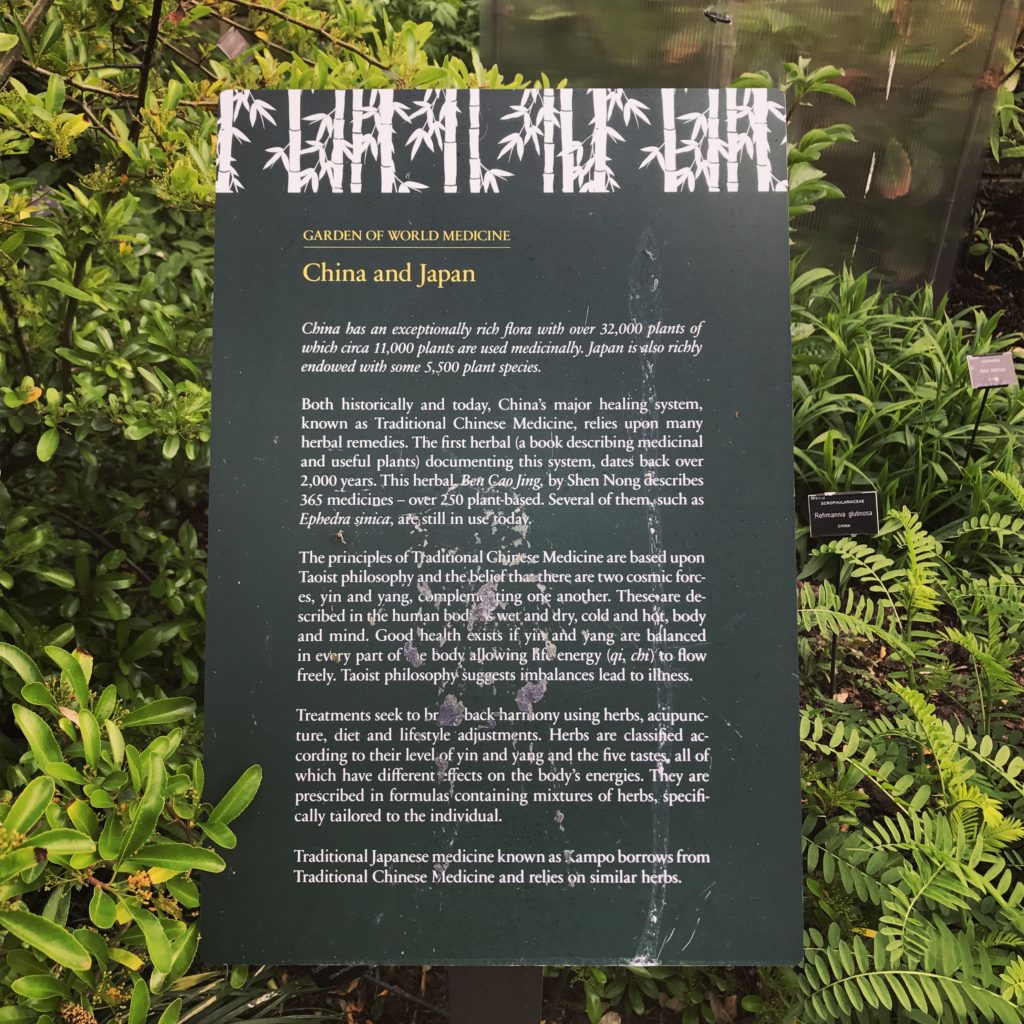

But what I found really intriguing this week was the subject of Native Remedies and how there is a feeling that a lot more research could be done into these areas…

The witness statement below is from Consultant Anaesthetist, Dr Mark Swerdlow

We set up a study in the early 1980s in three developed countries and three underdeveloped countries to see what the situation was at that time, what sort of treatment patients were receiving and what sort of pain relief, if any, they received. At that time I went to two or three very poor countries, to see cancer patients in hospital, and it was pathetic to see the worse-than-basic conditions within the hospitals. I remember the women’s ward in one hospital in Sri Lanka in particular – there must have been 12 or 14 women there with really advanced cancer – and as I walked round the ward, none of them seemed to be in great pain. I asked the young doctor who was in charge of this ward what treatment they were receiving. He said, ‘They get two tablets of aspirin a day’, and I just couldn’t believe it. I asked, ‘Do they not receive anything except two aspirin tablets a day? Don’t they get any sort of native herb treatment of any kind?’ He said, ‘Well, yes, they do get a native medication,’ and when I asked, ‘What’s in the native medication?’, he said, ‘Oh, I don’t know that.’ I have often wondered since then why somebody hasn’t gone out there to study those herbs and what’s in them, because they looked to be pretty effective.

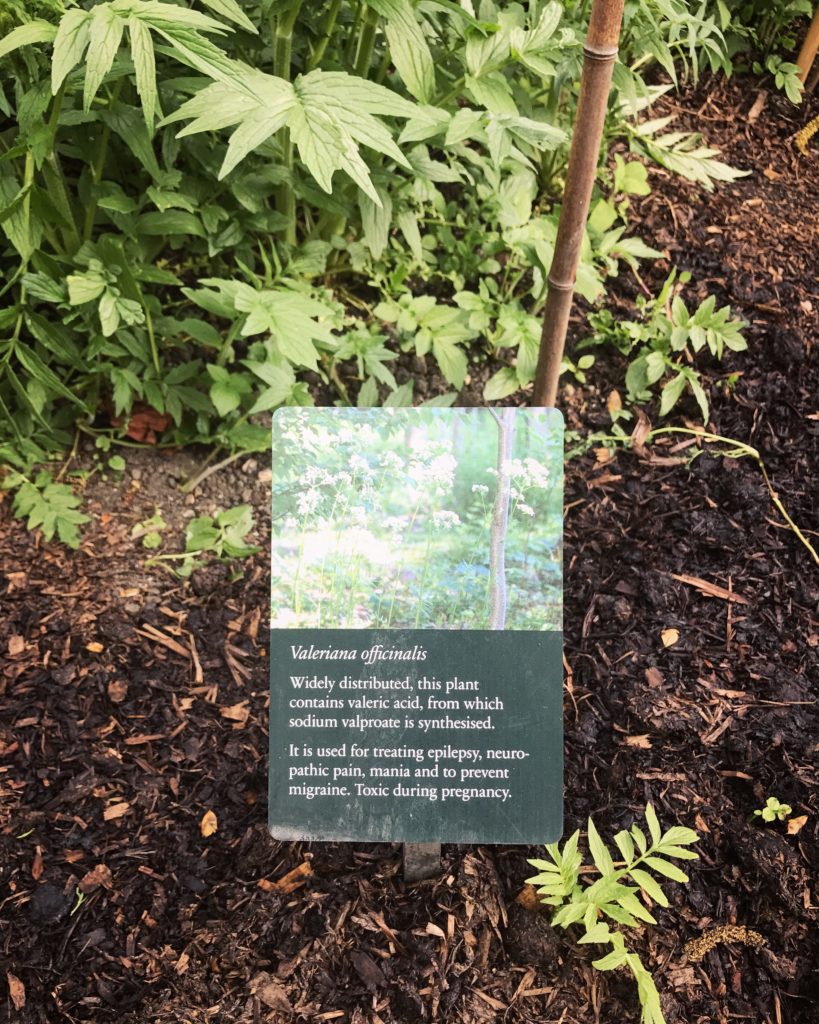

I felt quite ignorant discovering that the source of Aspirin was a perennial herb!

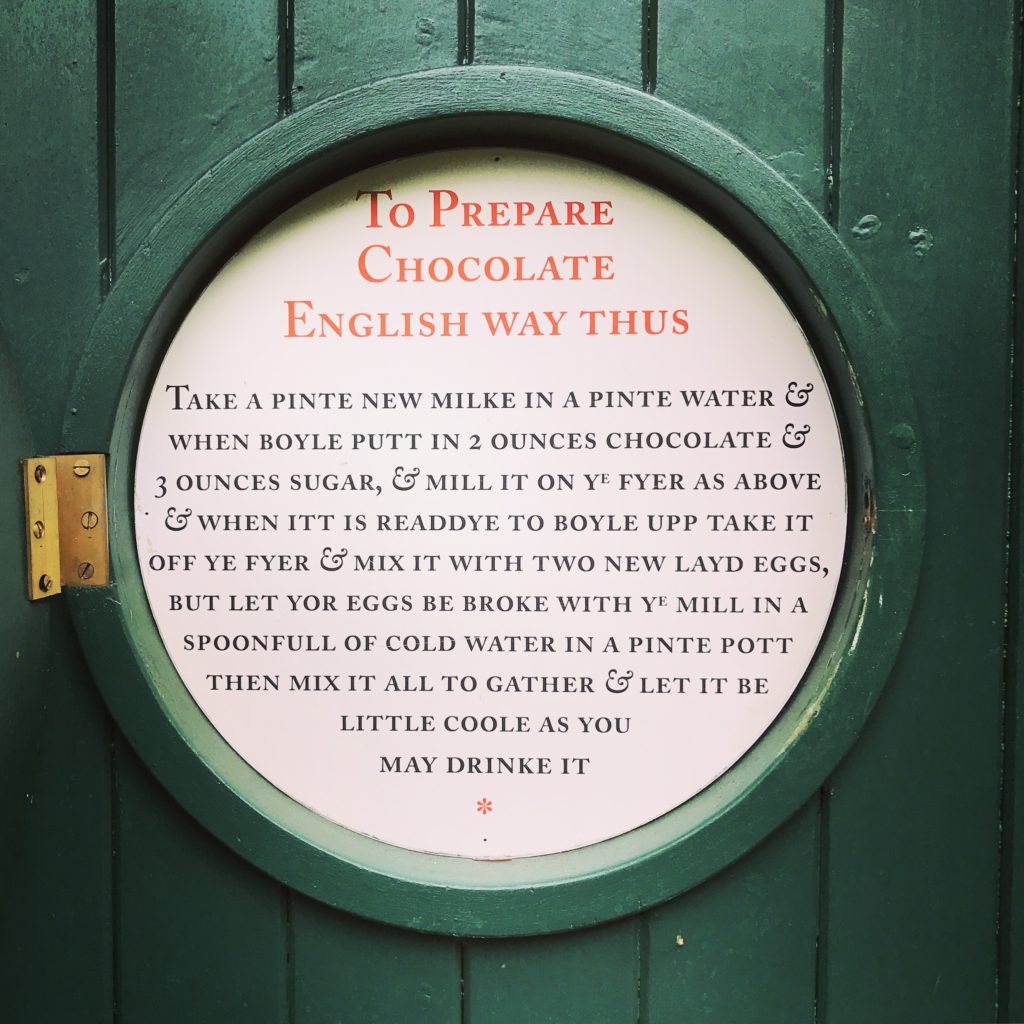

But I had absolutely no idea that it was actually synthesised from a plant called Valeriana Officinalis and there it was growing in Chelsea Physic Garden.

Another witness statement from Dame Cicely Saunders, physician and the founder of the Modern Hospice Movement concerning morphine is below:

At about the same time, in March 1948, I was impelled by the stories of my patients that I had experienced first as a nurse, but most of all as a social worker. I knew I had to do something about end-of-life pain and I went, as a State Registered Nurse volunteer, to one of the early homes. There I found that the nurses seeing the prescriptions of morphine four-hourly ‘PRN’, pro re nata,

as needed or as requested, by the doctors, quite quietly took ‘PRN’ off and gave the drug four-hourly, so as to prevent pain ever happening. This regular oral four-hourly giving of morphine dates back to 1935, fairly soon after the Brompton cocktail was put together. Now I was very impressed by this, because the patients were so much better with the pain control than the ones I had seen in hospital before then. During that time I took Mr Norman Barrett, the surgeon I was working for, to see this, and to visit a patient at home and so on. When I said to him, ‘I am going to have to go back and nurse the dying somehow,’ he said, ‘Go and read medicine. So many doctors desert the dying, and there’s so much more to be learnt about pain, and you will only be frustrated if you don’t do it properly, and they won’t listen to you.’ So I did read medicine.

There seem to be quite a few plants which have this duel capacity; my teenage son informed me that nutmeg can also be hallucinogenic and cause severe illness if taken in large quantities…( I think the quantities have to be pretty large though! )

A study on 6 mice who got better was heralded as ‘actual proof’, as opposed to research of 4500 patients, 1000 who got better, but which was said to be irrelevant because of the different quality of data.

However since 2010 Sativex, a specific extract of Cannabis , was approved as a botanical drug in the United Kingdom as a mouth spray to alleviate neuropathic pain, spasticity, overactive bladder, and other symptoms of multiple sclerosis .

Witness Statement below from Dr Geoffrey Guy, Industrial Pharmacologist

A large number of patients have reported, in the vernacular, that use of street cannabis in smoked, cooked or other forms, was giving them marked benefit. My temptation was to believe them. Why other people didn’t, I’m not sure. What was interesting when we started the programme was that as soon as we announced it, people started writing to us. We had a secret address and still do, but they wrote to the newspapers that covered the stories; they wrote to the BBC; they wrote to the Home Office. We used to receive a mailbag from the Home Office once a week. Over time, we had about 4500 patients who wrote to us and about 30 per cent of them had experience with cannabis. We then drew up, I think, a 70-point questionnaire and wrote back to them all. We wanted to know everything about what they did: where they found their cannabis; what type it was; whether they felt some was better than others; what caused them to take more; what caused them to take less – supply was the problem that caused patients to take less, not side effects – and what other medicines they’d been on. We found a very clear picture of what the material could do and what we had to do then was to try to maintain that. Information from David Baker’s research, and a lot of research throughout the world, was beginning to add biological and scientific credibility to a quality of data, which, sadly in this day and age, physicians don’t heed very well. I think it is at their risk that they don’t heed and don’t seem to listen to the patients. I know that David’s study was absolutely heralded as ‘the actual proof ’, in that six mice got better; so that was fine. The fact that we had 4,500 patients, 1,000 of whom had got better, was irrelevant, because it was a different quality of data.

And finally I wanted to touch on one of my favourite paragraphs from Witnesses To Modern Biomedicine by Dr César Milstein, Molecular Biologist, Immunologist and Nobel Laureate which has the heading of ‘Laziness’

Laziness is the mother of good science. Creation comes from moments when you don’t have anything to do. When you have no teaching, and basic admin, and extra commitments are seen to interfere with research, what if you have strong motivation, and don’t know what to do? If you are teaching, you can fill your gaps by teaching, but researchers have to fill the gaps with thoughts. Applications of science are important and socially attractive but they detract from the single mindedness of research.

I learnt more in unofficial discussion around the swimming pool, than I did from any of the formal presentations, because I met people, I talked to them informally, and I got many ideas and contacts from that very nice relaxing two hours. There is a lot to be said for not overburdening your conferences with too many papers.

Reading these statements reassures me that this is all just part of the process, both scientific and artistic and over the last couple of months since working on this project I have become more aware of creative similarities between researchers and artists.

This project has been a real journey of discovery and the stories and witness statements I have focused on here in Part 1, Part 2, Part 3 and this Part 4 are only the tip of the iceberg. Some of the other stories I found fascinating involved Facial Recognition, the Familigram, Self Experimentation, Obstetric Ultrasound and the first designs of the Ultrasound Scanner, but there are loads and if you are curious you really should have a read of Volume 50 which is an A–Z, comprising of a series of extracts from previous volumes, contributors include clinicians, scientists, patients and numerous others involved in modern biomedicine, in the UK and beyond. Topics in it range from ‘age discrimination’ to ‘Zantac’, and feature memories from every decade between 1930s and the present. The History of Modern Biomedicine Research Group hosted its first Witness Seminar, on monoclonal antibodies, in 1993 and since then more than sixty such meetings have been held. These all sought to go behind-the-scenes of contemporary biomedicine to find out ‘what really happened’.

I have genuinely been surprised at how inspired I have been artistically from science and medical based information and so excited when the science, the research, nature and art have all come together.

It has also meant that the ‘fear’ element of all things medical has definitely been shifted for me…my mother was SO right when she told me that if I took great interest in something it would become less intimidating, less fearful, and far more interesting, and I have personally found that I can now add ‘inspiring’ to that list of benefits.

You can look at the visual Steller Story version of this post here , my instagram posts here and some of my Pinterest inspiration for the whole project here.

You can also find out more about The Modern Biomedicine Research Group funded by The Wellcome Trust, on their website here , their Facebook page here , their YouTube Channel here and their Twitter account here.

Sarah Badman-Flook

Posted at 11:47h, 02 MayWow. What a fantastic and inspiring piece. I honestly have learnt so much! And my favourite part and one to remember was your mother quote at the end. Thank you for all the research, great photos and explaining it in layman’s terms. Sarah

5ftinf

Posted at 08:31h, 06 MayThanks so much Sarah, that’s so god to hear!! My mother has always given me some great pearls of advice over the years!( I thought of you with my new post today as there is some absolutely incredible enamelled lichen on a silver vesselwhich I saw at the V&A yesterday! )